Recently, I became rather obsessed with two small pieces in Defoe’s Review of March 27th, 1705 and the ‘Supplement of January 1705’ (published after March). They debate the extent to which dogs can reason. Researching the contexts for this involved a deep dive into the complex history of the debate about reasoning animals, the animal soul, and Descartes’ ‘beast-machine’ as outlined in his Discourse on Method. The debate spun across religious, philosophical, classical, literary, journalistic and scientific writings for over a century after. But I particularly needed to map out the writings published in the years immediately before Defoe’s 1705 piece.[1] The results revealed a gratifying surge in the English debate from around 1690. Below I’ve listed these, in chronological order, with some very brief notes to indicate their position. In addition, Charles Morton – Defoe attended Morton’s Newington Green Dissenting Academy – clearly engaged in the debate in his own teaching, in a section entitled ‘Appendix of the Soules of Brutes’ in his MS dissertation ‘Pneumaticks: Or the Doctrine of Spirits’ (Morton is skeptical about the beast-machine).

Recently, I became rather obsessed with two small pieces in Defoe’s Review of March 27th, 1705 and the ‘Supplement of January 1705’ (published after March). They debate the extent to which dogs can reason. Researching the contexts for this involved a deep dive into the complex history of the debate about reasoning animals, the animal soul, and Descartes’ ‘beast-machine’ as outlined in his Discourse on Method. The debate spun across religious, philosophical, classical, literary, journalistic and scientific writings for over a century after. But I particularly needed to map out the writings published in the years immediately before Defoe’s 1705 piece.[1] The results revealed a gratifying surge in the English debate from around 1690. Below I’ve listed these, in chronological order, with some very brief notes to indicate their position. In addition, Charles Morton – Defoe attended Morton’s Newington Green Dissenting Academy – clearly engaged in the debate in his own teaching, in a section entitled ‘Appendix of the Soules of Brutes’ in his MS dissertation ‘Pneumaticks: Or the Doctrine of Spirits’ (Morton is skeptical about the beast-machine).

T. Lucretius Carus the Epicurean philospher his six books De natura rerum done into English verse, with notes. Trans., Thomas Creech. Oxford: printed by L. Lichfield for Anthony Stephens, 1682. It had reached a fifth edition by 1700. (Creech’s notes acknowledge the possibility of animal rationality but not the logical consequence of the immortality of an animal soul).

Essays of Michael, Seigneur de Montaigne in Three Books. Trans., Charles Cotton. London, 1685. This had reached a third edition by 1700. (This is positive about animal rationality and willing to concede significant likenesses between human and animals).

Plutarch’s morals translated from the Greek by several hands. London: printed for T. Sawbridge, M. Gilliflower, R. Bently [and seven others], 1691; vol 5. Translations of the Moralia appeared from the 1680s, but only volume 5 included the two tales that debate animal rationality: ‘Which are more Crafty’ and ‘That Brute Beasts make use of Reason’. New editions in 1694 and 1704. (These two tales are sympathetic to animal reasoning).

John Ray, The wisdom of God manifested in the works of the creation being the substance of some common places delivered in the chappel of Trinity-College, in Cambridge. London: printed for Samuel Smith, 1691. Numerous expanded editions, including a fourth in 1704. (Strongly anti-Cartesian).

Gabriel Daniel, A voyage to the world of Cartesius written originally in French, and now translated into English. London: printed and sold by Thomas Bennet, 1692. (Satire on Cartesianism).

John Dunton, The Young-students-library containing extracts and abridgments of the most valuable books printed in England, and in the forreign journals, from the year sixty five, to this time … by the Athenian Society. London: printed for John Dunton, 1692. This contains That Beasts are meer Machines, divided into two Dissertations: At Amsterdam by J. Darmanson. (Anti-Cartesian).

Athenian Gazette, Feb 11, 1693. Reprinted in The Athenian oracle: being an entire collection of all the valuable questions and answers in the old Athenian mercuries. … By a member of the Athenian Society. London: printed for Andrew Bell, 1703-04. Vol. 1:504-507. (Goes over both sides of beast-machine debate).

Antoine Le Grande, An entire body of philosophy according to the principles of the famous Renate Des Cartes in three books, (I) the institution … (II) the history of nature … (III) a dissertation of the want of sense and knowledge in brute animals. Trans. Richard Blome. London, 1694. (Important dissemination of Descartes’s ideas in English).

‘The Turtle, or an Elegy, by Clarissa’, in, Gentleman’s Journal, or the Monthly Miscellany, III (August, 1694), 222.

Malebranch’s Search after truth. London: printed for J. Dunton, 1694-95. Trans. R. Sault. (Cartesian).[2]

John Norris, An essay towards the theory of the ideal or intelligible world. Part II. London: printed for S. Manship and W. Hawes [1701]. Vol. 2, the chapter entitled ‘A Digression concerning the Souls of Brutes, whether they have any Thought or Sensation in them or no?’ (Certainly perceived as Cartesian, but allows for some doubt about the absolute difference between human and animals). [3]

William Coward, Second thoughts concerning human soul. London: printed for R. Basset, 1702. (Argues that body and soul are one entity and so for the parity of human and animal soul).[4]

John Toland, Letters to Serena. London: printed for Bernard Lintot [1704]. (Mechanistic debate about motion that implies similarity between animal and human matter).

The image is a detail from ‘The Refreshment’, 1818. Courtesy Mills Library, McMaster University, and from the files of the McMaster journal Eighteenth-Century Fiction. http://eighteenthcenturyfiction.tumblr.com/

[1] I was aided by Erica Fudge’s Brutal Reasoning. Animals, Rationality, and Humanity in Early Modern England. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2006, Keith Thomas’s magisterial Man and the Natural World, 1500-1800 (1983), and Wallace Shugg’s earlier ‘The Cartesian Beast-Machine in English Literature (1663-1750)’ (Journal of the History of Ideas, 29: 2 (1968)). I was able to refine some of this research and find additional material via searches on ECCO, EEBO and the ESTC.

[2] Clearly, Dunton was deeply interested in disseminating all sides of the animal-machine debate coming from continental Europe.

[3] John Locke, letter, 21 March 1703-4. The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes, (London: Rivington, 1824 12th ed.). Vol. 9. http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=com_staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle=1726&layout=html

“Men of Mr. Norris’s way seem to me to decree, rather than to argue. They, against all evidence of sense and reason, decree brutes to be machines, only because their hypothesis requires it; and then with a like authority, suppose, as you rightly observe, what they should prove: viz. that whatsoever thinks, is immaterial.”

[4] Norris and Coward are particularly interesting because they are name-checked in Defoe’s The Consolidator: Or, Memoirs of Sundry Transactions From the World in the Moon, also published in 1705.

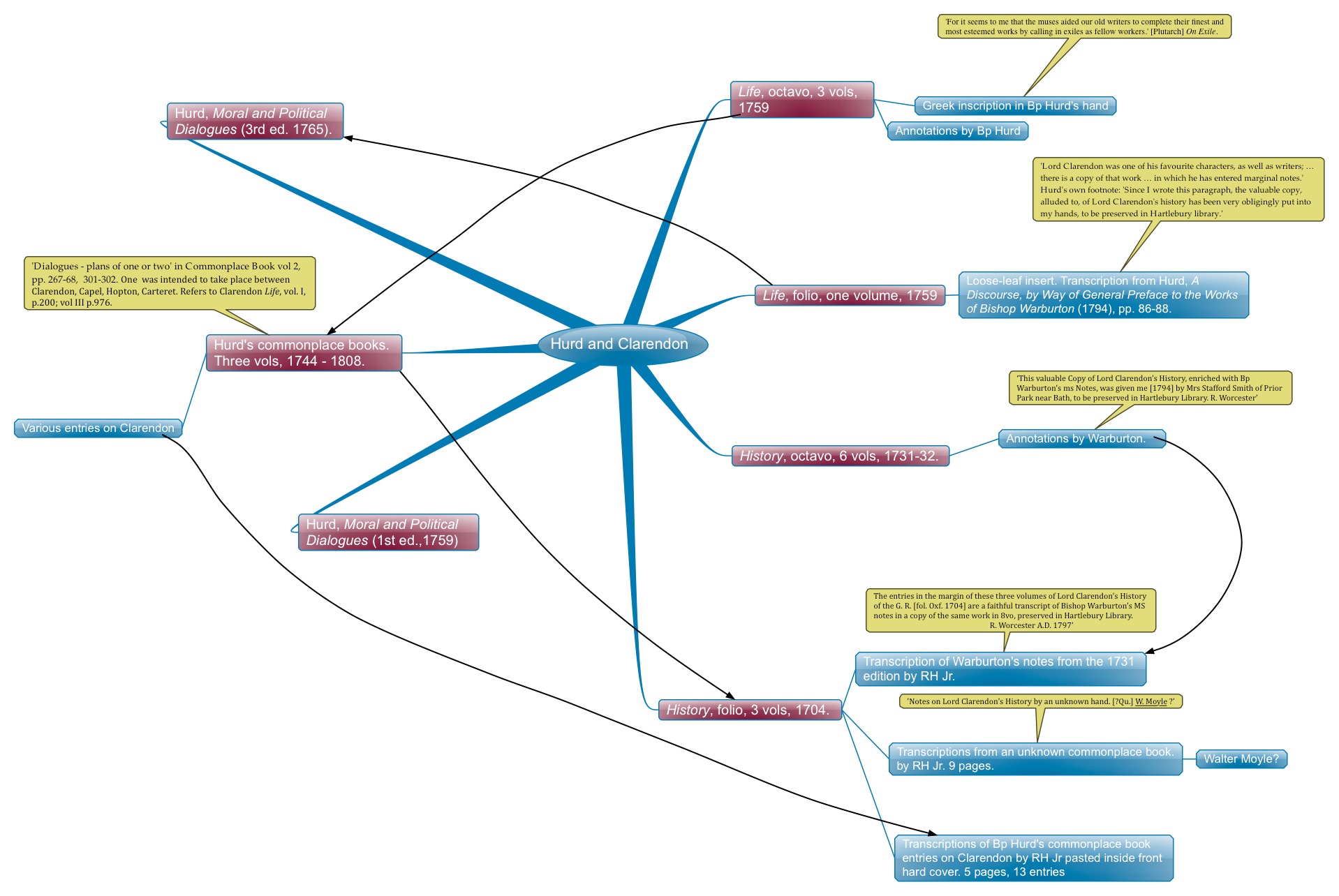

![[Click to enlarge]](https://hcommons-staging.org/app/uploads/sites/1002556/2013/03/hurd_clarendon1.png?w=490)